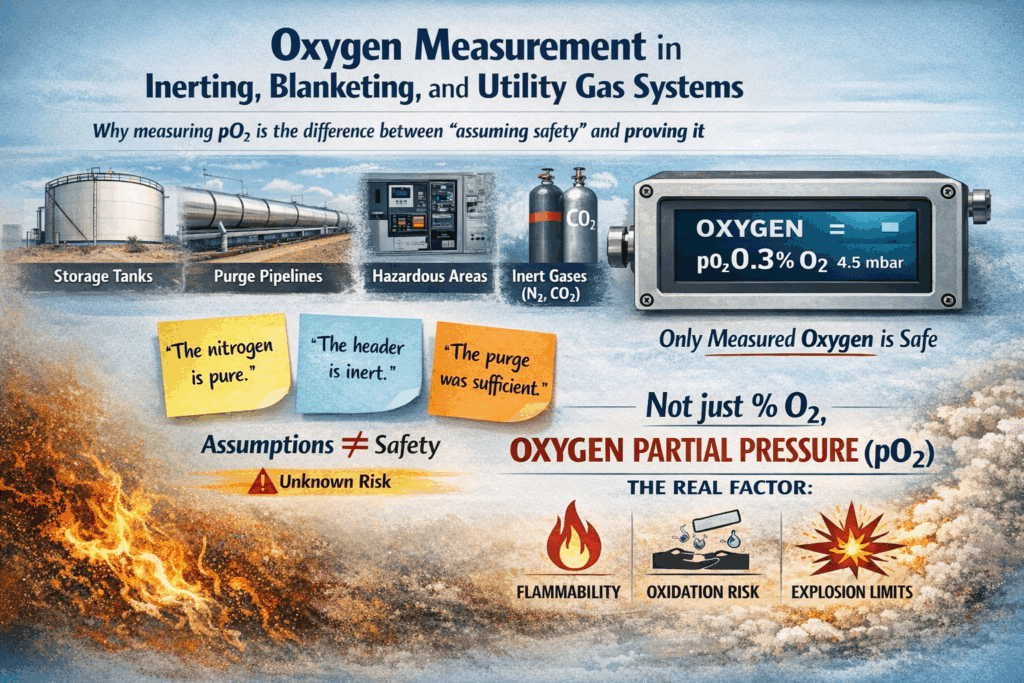

Oxygen Measurement in Inerting, Blanketing, and Utility Gas Systems

Why measuring pO₂ is the difference between “assuming safety” and proving it

In modern plants, inerting and blanketing are fundamental safety practices. Nitrogen, CO₂, and mixed inert gases are used everywhere: to protect storage tanks, purge pipelines, maintain non-flammable atmospheres, and safeguard hazardous-area equipment.

Yet in many facilities, these systems still operate on assumptions:

- “The nitrogen is pure.”

- “The header is inert.”

- “The purge was sufficient.”

From a safety and engineering standpoint, assumptions are not protection.

Only measured oxygen is.

And not just %O₂, but oxygen partial pressure (pO₂) – the real variable that defines flammability, oxidation risk, and explosion limits.

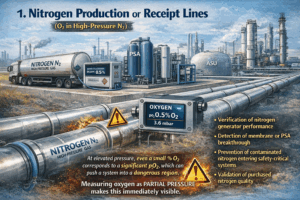

1. Nitrogen production or receipt lines

(O₂ in high-pressure N₂)

Whether nitrogen is produced on-site (PSA, membrane, ASU) or received by truck, its purity is never guaranteed by design alone.

Oxygen measurement here ensures:

- Verification of nitrogen generator performance

- Detection of membrane or PSA breakthrough

- Prevention of contaminated nitrogen entering safety-critical systems

- Validation of purchased nitrogen quality

At elevated pressure, even a small %O₂ corresponds to a significant pO₂, which can push a system into a dangerous region. Measuring oxygen as partial pressure makes this immediately visible.

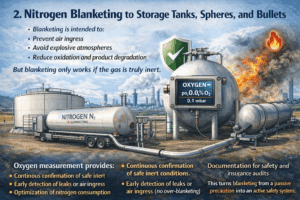

2. Nitrogen blanketing to storage tanks, spheres, and bullets

Blanketing is intended to:

- Prevent air ingress

- Avoid explosive atmospheres

- Reduce oxidation and product degradation

But blanketing only works if the gas is truly inert.

Oxygen measurement provides:

- Continuous confirmation of safe inert conditions

- Early detection of leaks or air ingress

- Optimization of nitrogen consumption (no over-blanketing)

- Documentation for safety and insurance audits

This turns blanketing from a passive precaution into an active safety system.

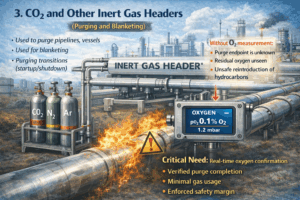

3. CO₂ and other inert gas headers

(Purging and blanketing services)

CO₂, argon, and mixed inert gases are widely used for:

- Vessel purging

- Pipeline inerting

- Startup and shutdown sequences

Without oxygen monitoring:

- You do not know when purging is complete

- You do not know if residual oxygen remains

- You risk unsafe reintroduction of hydrocarbons

With real-time oxygen measurement:

- Purge completion is verified, not guessed

- Gas usage is minimized

- Safety margins are demonstrably enforced

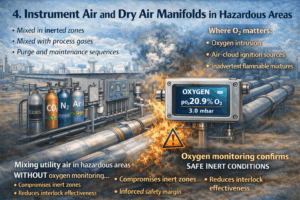

4. Instrument air and dry air manifolds in hazardous areas

Instrument air is often assumed to be “safe air.”

But in hazardous locations, oxygen content becomes critical when:

- Air is mixed with process gases

- Instruments operate in partially inerted zones

- Dry air is used during purge or maintenance sequences

Oxygen monitoring here:

- Confirms that instrument supply does not compromise inert zones

- Supports safe startup and commissioning procedures

- Prevents unintended creation of flammable mixtures

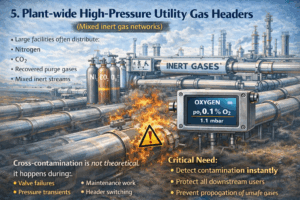

5. Plant-wide high-pressure utility gas headers

(Mixed inert gas networks)

Large facilities often distribute:

- Nitrogen

- CO₂

- Recovered purge gases

- Mixed inert streams

Cross-contamination is not theoretical. It happens during:

- Valve failures

- Maintenance work

- Pressure transients

- Header switching

Oxygen measurement at strategic points:

- Detects contamination instantly

- Protects all downstream users

- Prevents propagation of unsafe gas throughout the plant

Why oxygen must be measured as partial pressure

Oxygen does not act in isolation from pressure. In any gas mixture, each component contributes to the total pressure independently. This is Dalton’s law, and it is why oxygen must be evaluated as partial pressure (pO₂) and not only as a percentage.

The relationship between oxygen concentration and oxygen partial pressure is given by:

p(O₂) = x(O₂) × P(abs)

Where:

p(O₂) = Oxygen partial pressure

x(O₂) = Oxygen mole fraction (for example: 2% = 0.02)

P(abs) = Absolute system pressure

This equation shows that oxygen risk is a function of both concentration and pressure.

If pressure increases, oxygen becomes more dangerous even if the percentage stays the same.

Example:

Same 2% oxygen.

But the reactive oxygen availability increases 10–20×.

This directly affects:

- Ignition probability

- Flame propagation speed

- Explosion severity

- Oxidation reactions

Why %O₂ alone is misleading:

Volume percent assumes pressure is constant.

In real plants:

- Nitrogen headers run at 5–40 bar

- Electrolyzer oxygen lines operate at high pressure

- Utility gas systems are pressurized

- Inerting and purging are done under pressure

A reading of “1% O₂” may look safe, but at high pressure it can already be in a flammable or reactive regime.

Why flammability depends on pO₂:

Flammability limits and explosion behavior depend on:

- Number of oxygen molecules per unit volume

- Collision frequency between oxygen and fuel molecules

- Reaction kinetics

All of these scale with partial pressure, not percent.

Higher pO₂ means:

- Faster reaction rates

- Lower ignition energy

- Wider flammability window

- More severe combustion

Why modern safety systems use pO₂:

Using %O₂:

- Hides pressure effects

- Underestimates risk at high pressure

- Creates false sense of safety

Using pO₂:

- Directly represents chemical reactivity

- Automatically accounts for pressure

- Gives one consistent safety variable for all operating conditions

- Allows meaningful alarm thresholds independent of system pressureEngineering interpretation:

That is why in safety-critical applications:

- Inerting systems

- Flare headers

- Electrolyzers

- Nitrogen utilities

- High-pressure purge systems

Oxygen must be treated as a pressure-dependent hazard variable, not merely a concentration.

In simple terms:

%O₂ tells you “how much oxygen is mixed in.”

pO₂ tells you “how dangerous that oxygen really is.”

Why optical, in-situ oxygen measurement is ideal for these applications

For inerting and utility systems, the analyzer must be:

- Fast

- Stable

- Immune to interference

- Maintenance-light

- Safety-certified

Optical fluorescence-based analyzers like MOD-1040 provide:

- Direct measurement of oxygen partial pressure

- No oxygen consumption

- Immunity to hydrocarbons, H₂S, CO₂, and moisture

- In-situ installation (no sampling systems)

- Fast response for purge and inerting transitions

- ATEX / IECEx and SIL-2 suitability

This makes oxygen a measured safety variable, not an assumed condition.

From Modcon perspective: inerting is not a utility. It is a control function.

Inerting, blanketing, and utility gas systems form a hidden safety layer in every plant.

When oxygen is not measured, that layer is blind.

When oxygen is measured:

- Safety becomes quantifiable

- Purge processes become efficient

- Nitrogen usage becomes optimized

- Risk becomes manageable

In short: You don’t make a system safe by injecting inert gas. You make it safe by proving oxygen is not there.