Oxygen Control in Ammonia and Syngas Production

Protecting Catalysts, Ensuring Safety, and Preserving Process Economics

Introduction, Chemical Reality, and Economic Impact

-

Oxygen: The Most Dangerous Trace Contaminant in Process Gas

In ammonia and syngas production, oxygen is not simply another impurity. It is one of the most destructive contaminants that can enter a process. While many impurities affect efficiency or yield gradually, oxygen acts immediately and often irreversibly. Even concentrations measured in parts per million can trigger oxidation reactions that permanently damage catalysts, compromise reactor integrity, and destabilize entire production trains.

This is what makes oxygen fundamentally different from most other trace components. Sulfur, moisture, or CO₂ may degrade performance over time, but oxygen has the ability to terminate catalytic activity in minutes. It attacks the very surface that enables the chemistry to occur. Once that surface is oxidized, it can rarely be restored to its original activity.

Despite this, oxygen is often treated as a secondary parameter in hydrogen and syngas systems. It is sometimes monitored intermittently, sometimes inferred indirectly, and sometimes not measured at all. In many facilities, oxygen control relies more on procedural discipline than on continuous verification. This creates a blind spot in processes that otherwise operate with extremely high technical rigor.

In modern ammonia and syngas plants, where catalysts represent tens of millions of dollars in capital investment and unplanned downtime can cost millions per day, this blind spot is no longer acceptable. Oxygen must be treated as a primary process variable, not a background impurity. Continuous, real-time oxygen measurement at the ppm level becomes a fundamental layer of process protection.

-

The Chemistry of Catalyst Oxidation

The catalysts used in ammonia synthesis and syngas-based processes are designed to operate in strongly reducing environments. Iron-based catalysts in ammonia synthesis, nickel-based catalysts in reforming and hydrogenation, and copper-based catalysts in shift and methanol synthesis are all highly sensitive to oxygen.

These catalysts rely on metallic active sites to function. Oxygen reacts with these sites to form oxides, which are chemically stable and catalytically inactive. This reaction is not gradual. It is fast, highly exothermic, and often irreversible under normal operating conditions.

For example, in ammonia synthesis:

- The iron catalyst surface must remain in a reduced metallic state.

- Exposure to even a few ppm of oxygen can oxidize active sites.

- Oxidation reduces surface area and catalytic activity.

- The catalyst loses efficiency and requires higher temperatures and pressures to achieve the same conversion.

In syngas systems:

- Nickel catalysts can be rapidly oxidized.

- Copper-based catalysts are even more sensitive.

- Partial oxidation of catalyst beds leads to hot spots, mechanical stress, and long-term degradation.

The key point is that oxygen does not simply “contaminate” the process. It fundamentally changes the chemical state of the catalyst. That is why oxygen control is not about product purity; it is about preserving the functional heart of the plant.

- The Economic Consequences of Oxygen Ingress

Catalysts represent one of the largest single investments in ammonia and syngas plants. Replacement costs can range from several million to tens of millions of dollars, depending on unit size and catalyst type. But the true cost of catalyst damage is far higher than the price of the material itself.

When oxygen causes catalyst degradation, the consequences cascade:

- Reduced conversion efficiency

- Higher energy consumption

- Increased recycle flows

- Loss of throughput

- Off-spec production

- Forced shutdowns for regeneration or replacement

A single oxygen ingress event can reduce catalyst lifetime by months or even years. In severe cases, the catalyst bed must be replaced immediately, turning a minor contamination incident into a major operational crisis.

Furthermore, catalyst damage rarely appears instantly as a shutdown. It often begins as:

- Slightly higher temperatures

- Slightly higher pressure drop

- Slightly lower conversion

These symptoms are frequently misinterpreted as normal process variation. By the time the root cause is identified, the damage is already done.

This is why oxygen must be measured continuously, not sampled occasionally. Oxygen ingress is not a statistical risk. It is a deterministic chemical threat.

-

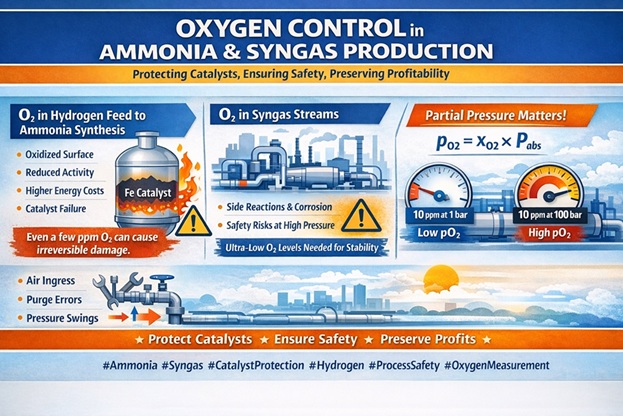

Oxygen in Hydrogen Feed to Ammonia Synthesis

The hydrogen feed to the ammonia synthesis loop is one of the most critical measurement points in the entire plant. This is the last barrier protecting the catalyst from contamination.

Hydrogen streams may appear chemically pure, but oxygen can enter through:

- PSA breakthrough

- Membrane leakage

- Valve seat leaks

- Maintenance errors

- Incomplete purging

- Atmospheric ingress during pressure transients

Without continuous oxygen monitoring, these events can go unnoticed until catalyst performance begins to decline.

At this point, oxygen measurement serves three simultaneous purposes:

- Catalyst Protection

It prevents irreversible oxidation by detecting contamination before damage occurs.

- Safety

Hydrogen and oxygen mixtures create explosive atmospheres. Even trace oxygen at high pressure increases the partial pressure of oxygen significantly, pushing the system toward dangerous flammability limits.

- Process Integrity

It ensures the synthesis loop operates within its true design envelope, not an assumed one.

In modern ammonia plants, oxygen monitoring in hydrogen feed should be treated with the same importance as pressure, temperature, or flow. It is not an optional measurement. It is a core safety and asset protection variable.

-

Oxygen in Syngas Streams

Syngas is the backbone of multiple industrial value chains. It feeds ammonia synthesis, methanol production, Fischer–Tropsch units, hydrogen purification systems, and a wide range of hydrogenation processes. In all of these applications, syngas is expected to be strongly reducing and free from oxidizing species. Oxygen presence in syngas fundamentally violates this assumption.

Unlike hydrogen-only streams, syngas contains carbon monoxide, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, methane, and traces of water. This chemical complexity makes oxygen contamination even more dangerous. Oxygen can:

- Oxidize metallic catalyst surfaces

- Promote unwanted side reactions

- Accelerate corrosion in downstream equipment

- Create local hot spots due to partial combustion

- Alter reaction kinetics and selectivity

In reforming and shift reactors, oxygen reacts directly with CO and H₂, generating heat and disturbing thermal balance. These micro-combustion events may not be visible in standard process instrumentation, but they contribute to catalyst sintering, mechanical stress, and long-term degradation.

In methanol synthesis and Fischer–Tropsch units, oxygen leads to:

- Oxidation of copper or cobalt catalysts

- Loss of activity and selectivity

- Increased formation of undesired by-products

- Higher recycle ratios and energy penalties

What makes syngas particularly sensitive is its high operating pressure. At elevated pressure, even very small oxygen concentrations translate into significant oxygen partial pressure. A few ppm at 100 bar represent a far more aggressive oxidizing environment than the same concentration at atmospheric conditions.

Therefore, oxygen in syngas streams must be treated as a primary integrity variable, not as a trace impurity. Continuous monitoring provides the only reliable protection mechanism.

-

Catalyst Protection During Start-Up, Shutdown, and Transient Conditions

Most catalyst damage does not occur during stable, steady-state operation. It occurs during transitions.

Start-up, shutdown, load changes, and emergency trips create conditions where oxygen ingress is far more likely:

- Pressure is changing

- Flow direction may reverse

- Valves are moving

- Purge sequences are executed

- Equipment is not yet thermally stable

During these periods, even small procedural errors can introduce air into process lines. If oxygen enters while catalysts are hot and reduced, oxidation is immediate and severe.

Typical risk scenarios include:

- Incomplete inerting before hydrogen introduction

- Residual air pockets in piping

- Leakage through valve seats during pressure equalization

- PSA or membrane units not yet stabilized

- Operator assumption that “purge is complete”

Without real-time oxygen measurement, these events remain invisible. By the time abnormal reactor behavior is observed, catalyst damage has already begun.

Real-time ppm-level oxygen monitoring during transients allows:

- Immediate detection of oxygen ingress

- Verification of purge effectiveness

- Safe acceleration of start-up sequences

- Reduction of unnecessary conservatism

- Shorter commissioning and restart times

In modern plants, oxygen analyzers are not only protection devices. They are enablers of faster, safer, and more predictable operation.

-

Why ppm-Level Oxygen Measurement Is Technically Challenging

Measuring oxygen in the 0–100 ppm range is fundamentally different from measuring oxygen in percent ranges. At ppm levels, the signal becomes extremely small relative to environmental disturbances.

Key challenges include:

- Leakage and permeation

Even tiny air leaks in sampling systems, tubing, or fittings can introduce oxygen concentrations larger than the true process value. This makes extractive systems inherently risky at low ppm levels.

- Outgassing from materials

Elastomers, seals, and plastics release absorbed oxygen over time, contaminating samples.

- Moisture interference

Water vapor affects many sensor technologies and can distort oxygen readings through dilution or reaction effects.

- Drift and zero instability

At ppm levels, sensor drift becomes comparable to the signal itself. Maintaining long-term stability is extremely difficult.

- Response time

In extractive systems, transport delays and conditioning systems mask fast oxygen ingress events, exactly when detection is most critical.

This is why traditional electrochemical or paramagnetic sensors struggle in ultra-low oxygen applications. They were designed for bulk gas analysis, not for catalyst protection and safety-critical monitoring.

For oxygen measurement to become a true process protection variable, it must be:

- In-situ

- Fast

- Stable

- Immune to moisture

- Independent of sampling systems

-

Why Partial Pressure (pO₂) Matters More Than %O₂

Most oxygen analyzers report oxygen as a mole fraction: ppm or %. While convenient, this representation hides the true physical risk.

The parameter that determines chemical reactivity, oxidation potential, and flammability is oxygen partial pressure:

p_{O2} = x_{O2} × P_{abs}

Where:

- p_{O2} is the oxygen partial pressure

- x_{O2} is the oxygen mole fraction

- P_{abs} is the absolute process pressure

This equation reveals a critical truth:

At higher pressure, the same oxygen concentration becomes far more dangerous.

Examples:

- 10 ppm O₂ at 1 bar → pO₂ = 0.00001 bar

- 10 ppm O₂ at 100 bar → pO₂ = 0.001 bar

That is a 100× increase in oxidizing power for the same ppm reading.

This means that ppm limits defined at atmospheric pressure become meaningless at high pressure. What matters is the actual oxygen chemical potential acting on catalysts and materials.

By measuring oxygen as partial pressure rather than concentration alone, operators gain:

- A pressure-independent safety metric

- A physically meaningful control variable

- A direct indicator of oxidation risk

This is especially critical in ammonia and syngas plants, where high pressure is intrinsic to the process.

In such environments:

- ppm numbers can be misleading

- Partial pressure tells the real story

-

Comparison of Oxygen Measurement Technologies

Historically, oxygen has been measured using several different sensor technologies. Each has its strengths, but not all are suitable for ultra-low ppm, high-pressure, safety-critical environments such as ammonia and syngas production.

The most common technologies include:

Electrochemical (galvanic) sensors

These are widely used for portable and low-cost applications. They generate a current proportional to oxygen concentration through a chemical reaction.

Limitations:

- Limited lifetime due to electrolyte consumption

- Strong sensitivity to moisture and temperature

- Drift at low ppm levels

- Not suitable for continuous high-pressure operation

- Slow recovery after oxygen exposure

They are useful for spot checks, but not for permanent protection of critical catalysts.

Paramagnetic analyzers

These rely on the paramagnetic property of oxygen and are widely used in combustion control.

Limitations:

- Designed mainly for percent-level measurements

- Reduced sensitivity and stability in ppm ranges

- Sensitive to vibration, pressure variation, and flow conditions

- Usually require extractive sampling systems

They are excellent for combustion air monitoring but poorly suited for ultra-low oxygen purity control.

Zirconia sensors

Zirconia sensors measure oxygen based on electrochemical potential across a solid electrolyte at high temperature.

Limitations:

- Require high operating temperatures

- Sensitive to reducing gases (H₂, CO)

- Not stable at very low oxygen concentrations

- High drift when process composition varies

- Incompatible with hydrogen-rich streams without special conditioning

In ammonia and syngas service, zirconia sensors are generally unsuitable.

Optical fluorescence-based sensors

These measure oxygen by detecting how oxygen molecules quench the fluorescence lifetime of a sensing material. The effect is directly related to oxygen partial pressure.

Advantages:

- True partial pressure measurement

- Extremely high sensitivity at ppm levels

- No consumption of oxygen

- No drift from chemical aging

- Fast response time

- Stable over years

- Immune to hydrogen, CO, CO₂, and hydrocarbons

- Works in wet or dry gas

This makes fluorescence-based optical sensors uniquely suitable for:

- Hydrogen

- Syngas

- High-pressure inert systems

- Catalyst protection applications

They convert oxygen measurement from an approximation into a physically correct, pressure-aware process variable.

-

Why In-Situ Optical Measurement Is a Structural Advantage

In ultra-low oxygen measurement, how the gas reaches the sensor is often more important than the sensor itself. Traditional extractive systems introduce:

- Long sample lines

- Pressure reduction

- Moisture condensation

- Air ingress risk

- Response delays

All of these destroy measurement credibility in ppm-level applications.

In-situ optical measurement reverses the architecture:

Instead of moving the gas to the analyzer, the measurement is performed directly in the process, and only light travels to the electronics.

This creates several structural advantages:

- No sample transport

- No contamination risk

- No moisture conditioning

- No pressure reduction artifacts

- Immediate response to real process changes

The result is a measurement that reflects true process reality, not a conditioned approximation.

In hydrogen and syngas plants, this is decisive. Oxygen ingress often happens suddenly. Only an in-situ measurement can detect it before damage occurs.

-

Safety Implications: Flammability and Explosion Risk

Oxygen in hydrogen and syngas systems is not only a catalyst risk. It is also a direct explosion hazard.

Hydrogen-oxygen mixtures have extremely wide flammability limits and very low ignition energy. At high pressure, even trace oxygen dramatically increases explosion potential.

Key risks include:

- Formation of explosive mixtures in pipelines

- Detonation risk in compressors

- Fire hazard in purification units

- Increased danger during start-up and shutdown

Again, partial pressure is the determining variable.

At 100 bar:

- 10 ppm O₂ corresponds to a much higher oxidizing potential than most engineers intuitively assume.

- A small leak becomes a large energy source.

Real-time oxygen partial pressure measurement therefore becomes part of the plant’s primary safety system, not just quality control.

It allows:

- Immediate alarms

- Automatic isolation

- Controlled shutdown sequences

- Protection of personnel and assets

-

Oxygen Control as a Foundation of Process Stability

Catalyst health, safety, and process stability are inseparable.

When oxygen enters a hydrogen or syngas system:

- Catalysts degrade

- Reaction kinetics change

- Temperature profiles shift

- Control loops become unstable

- Operators lose predictability

What starts as a chemical issue becomes a control problem.

Continuous oxygen measurement stabilizes the entire process by:

- Ensuring catalysts remain in their intended chemical state

- Preserving predictable reaction behavior

- Maintaining stable energy balances

- Protecting downstream equipment

It becomes a foundation variable, like pressure or temperature.

In plants that treat oxygen measurement as optional, stability is achieved through conservatism. In plants that measure oxygen continuously, stability is achieved through knowledge.

-

Impact on Energy Efficiency

Energy efficiency in ammonia and syngas plants is closely tied to catalyst performance and process stability. When catalysts operate in their optimal chemical state, reactions proceed at lower activation energy, heat profiles remain predictable, and conversion efficiency is maximized. Oxygen contamination undermines all of these advantages.

Even minor oxidation of catalyst surfaces forces operators to compensate by:

- Increasing reactor temperature

- Raising compression ratios

- Increasing recycle flows

- Extending residence times

All of these responses consume additional energy. In ammonia synthesis, where energy intensity is already high, this penalty is significant. A small drop in catalyst activity can translate into several percent increase in energy consumption across the entire plant.

Continuous oxygen measurement protects energy efficiency by maintaining catalysts in their optimal reduced state. Instead of reacting to declining performance, operators prevent the cause itself. This stabilizes:

- Reactor heat balance

- Conversion efficiency

- Compressor loading

- Overall plant power demand

In syngas systems, oxygen control also avoids micro-combustion reactions that generate uncontrolled heat. These reactions increase cooling demand, disturb temperature profiles, and force conservative operation.

Thus, oxygen monitoring is indirectly an energy optimization tool. It preserves the chemical integrity that allows the plant to operate at its design efficiency.

- Integration into Control Systems and DCS

For oxygen measurement to deliver real value, it must be fully integrated into the plant’s control architecture. A standalone analyzer that only displays data locally does not protect catalysts or processes. The measurement must become part of the operational logic.

Integration typically includes:

- Direct signal input to the DCS

- Trending and historical analysis

- Alarm and interlock generation

- Use as a permissive for critical actions

- Feedback to purge and inerting sequences

In hydrogen and syngas plants, oxygen measurement is often linked to:

- Start-up permissives

- Catalyst reduction procedures

- PSA or membrane performance monitoring

- Compressor and reactor safety logic

The goal is not only detection, but prevention. If oxygen rises above defined thresholds:

- Hydrogen feed can be isolated

- Purge rates can be increased

- Units can be safely ramped down

- Operators can intervene before damage occurs

When oxygen analyzers are treated as part of the control system, they move from “instrumentation” to “process protection infrastructure.”

-

Alarm Philosophy and PASS (Process Alarm and Safety System)

Oxygen measurement belongs naturally in the PASS layer because it is directly tied to hazard prevention and asset protection.

However, alarm design must be intelligent. Poorly designed alarms lead to:

- Nuisance alerts

- Alarm flooding

- Operator desensitization

- Ignored safety signals

An effective alarm philosophy uses oxygen measurement in multiple tiers:

- Advisory level

Indicates rising oxygen trends. Operators can investigate before action is required.

- Warning level

Signals abnormal ingress. Automatic process adjustments may be triggered.

- Trip or interlock level

Protects catalysts and equipment by isolating affected systems.

Because oxygen analyzers measure partial pressure, alarm thresholds can be defined in physically meaningful units. This makes alarm settings robust across pressure variations and operating modes.

PASS integration allows:

- Early hazard detection

- Controlled, proportional response

- Elimination of unnecessary conservatism

- Stronger protection with fewer shutdowns

Instead of treating safety as binary (safe or unsafe), the plant gains a graduated protection model.

-

CAPEX and OPEX Implications

Traditional oxygen measurement systems rely on extractive sampling:

- Heated lines

- Pressure reduction

- Sample conditioning

- Analyzer shelters

- Purging systems

This architecture is expensive and fragile. It drives both capital cost and maintenance burden.

In-situ optical oxygen measurement transforms the economics:

CAPEX benefits:

- No analyzer shelters

- No long sample lines

- No gas conditioning systems

- Reduced hazardous-area infrastructure

- Simplified installation

One analyzer platform can often support multiple measurement points via optical multiplexing, reducing duplication.

OPEX benefits:

- No consumables

- No sensor degradation

- Minimal calibration

- High long-term stability

- No sample system maintenance

The analyzer becomes a low-maintenance asset rather than a service-intensive liability.

From a business perspective, this changes how oxygen measurement is justified:

- Not as a compliance cost

- But as a protection investment

- With measurable ROI through:

- Extended catalyst lifetime

- Reduced downtime

- Lower energy consumption

- Improved safety margins

This makes oxygen monitoring financially self-sustaining rather than an overhead.

-

Generic Case Study Logic: From Measurement to Protection

Although every ammonia and syngas plant has its own specific configuration, the logic of oxygen protection follows a universal pattern. A typical implementation can be summarized in four layers:

- Measurement Layer

An in-situ optical oxygen analyzer is installed directly in the hydrogen or syngas stream. The sensor continuously measures oxygen partial pressure with ppm sensitivity and fast response. There is no sample transport, no conditioning system, and no delay between the real process and the measured signal.

- Control Layer

The oxygen signal is integrated into the DCS and used for:

- Trending and diagnostics

- Performance validation of PSA or membrane units

- Verification of purge effectiveness

- Protection of catalyst reduction and activation steps

- Safety Layer (PASS)

Oxygen thresholds are defined in partial pressure units and structured in levels:

- Advisory: trend deviation

- Warning: abnormal contamination

- Trip/interlock: protection of equipment and catalysts

This creates a graded safety response instead of binary shutdown logic.

- Optimization Layer

Over time, oxygen data becomes part of process optimization:

- Identifying weak points in purging procedures

- Improving start-up speed safely

- Minimizing inert gas consumption

- Increasing availability and reliability

The plant evolves from reactive oxygen control to predictive oxygen management.

-

Best Practices for Analyzer Installation

Successful ultra-low oxygen measurement depends as much on installation philosophy as on sensor technology.

Key best practices include:

- True in-situ installation

Avoid extractive systems whenever possible. Measurement must occur directly in the pressurized stream.

- Short optical path

The sensing point should be close to the area being protected: upstream of catalysts, downstream of purification units, or at the interface between safety-critical sections.

- Stable mechanical mounting

Avoid vibration and mechanical stress. Optical sensors are robust but require good mechanical design.

- Electrical and optical isolation

Fiber optics allow electronics to remain in safe areas, improving reliability and reducing hazardous-area certification complexity.

- Clear alarm strategy

Define alarm limits in pO₂, not in ppm. This ensures pressure-independent safety logic.

- Integration with procedures

Oxygen measurement should be embedded into:

-

- Start-up sequences

- Catalyst activation

- Purge verification

- Shutdown procedures

The analyzer must be part of the operational culture, not just an instrument.

-

Oxygen Control and the Hydrogen Economy

The transition toward a hydrogen-based energy system amplifies the importance of oxygen control. Electrolyzers, hydrogen storage, transport systems, and downstream hydrogen applications all face the same fundamental challenge: hydrogen must remain free of oxygen to be safe and usable.

What ammonia and syngas plants have learned over decades is now becoming directly applicable to:

- Green hydrogen production

- Hydrogen compression and storage

- Hydrogen refueling infrastructure

- Hydrogen blending into natural gas networks

In electrolyzers, oxygen measurement:

- Protects membranes and stacks

- Detects crossover events

- Ensures hydrogen purity

In hydrogen storage and transport:

- Prevents formation of explosive mixtures

- Ensures regulatory compliance

- Preserves material integrity

Thus, oxygen measurement becomes one of the core enabling technologies of the hydrogen economy. The same principles developed for ammonia and syngas plants now define the safety architecture of future hydrogen systems.

Oxygen control in ammonia and syngas production is not a secondary quality parameter. It is a fundamental pillar of process safety, catalyst protection, energy efficiency, and economic stability.

At ppm levels and high pressures, oxygen is no longer a “trace impurity.” It becomes a powerful oxidizing agent capable of destroying catalysts, destabilizing reactors, and creating explosive conditions. Only continuous, real-time measurement based on oxygen partial pressure provides a physically correct and operationally reliable solution.

The evolution from extractive, slow-response analyzers to in-situ optical measurement represents a structural shift in how oxygen is monitored and controlled. It transforms oxygen measurement from a compliance activity into a core protection mechanism.

When integrated into:

- DCS

- PASS

- Start-up and shutdown procedures

- Optimization strategies

oxygen analyzers become part of the plant’s nervous system.

They protect assets, stabilize operation, reduce energy consumption, and create the foundation for intelligent, safe, and efficient chemical production.

This same philosophy now extends naturally into hydrogen systems, proving that oxygen control is not only about protecting the past, but about enabling the future.